- June 10, 2021

- Author: Ayoki Milton

- Category:

From the opening moments of his presidency, Donald Trump set forth a radically altered vision for the United States and its dealings with the rest of the world—one he dubbed “America First” , which seeks out for American workers and American interests (Washington Post). Under his ‘America First’ agenda, Trump has threatened to withdraw from the North American free-trade agreement (NAFTA), disavowed the global climate change accord and criticized global institutions including the United Nations, NATO and the WTO. And it remains to be seen in terms of the commercial front and the development what the agenda for Africa is from Trump Administration.

In the first year of his administration, Trump exhibited no interest in Africa; nor had any of his closest White House advisors. Trump first mentioned the commercial opportunities of the continent during his UN speech, but then that was undermined by him walking out of the meeting during the Africa session of the G-20 meeting at a time when Germany was pushing for an important Africa agenda. After two years of anxious waiting, African leaders are now beginning to see the dotted outlines of what Trump Africa policy is.

Finally, trade and investment appears to be a second-tier priority for the Trump administration in Africa. The question now is whether or not the Trump Administration plans to follow up on the programs started by previous administrations particularly the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), a landmark piece of legislation, which was signed into law by President Clinton in May 2000. AGOA’s objective is to expand U.S. trade and investment with sub-Saharan Africa, and to stimulate economic growth, encourage economic integration, and facilitate sub-Saharan Africa’s integration into the global economy. AGOA is a non-reciprocal trade preference that, along with those under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP), provides eligible sub-Saharan African countries with duty-free access to the U.S. market for over 2,300 products (i.e. over 1800 products under AGOA plus more than 5,000 products that are eligible under the GSP program). Recent evidence shows that AGOA indeed helped Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries eligible for AGOA benefits to expand their exports to the U.S.

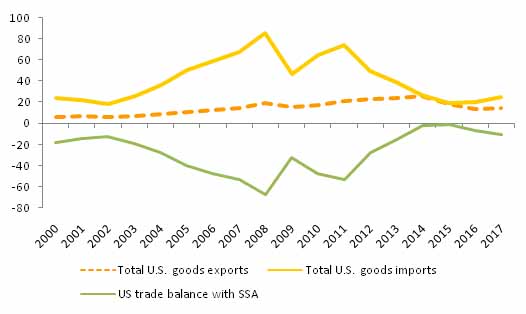

Figure 1 shows U.S. exports and imports from the 49 Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries, and AGOA imports from the SSA countries eligible for AGOA benefits. U.S. goods exports were $14.1 billion in 2017, down from $18.0 billion in 2015 (partly due to lower aircraft sales), while U.S. goods imports were $24.9 billion, up from $18.8 billion in 2015 (primarily due to rising commodity prices). As of January 1, 2019, 39 sub-Saharan African countries are eligible for AGOA benefits.

Figure 1. Goods Trade between the United States and Sub-Saharan Africa(billions of dollars)

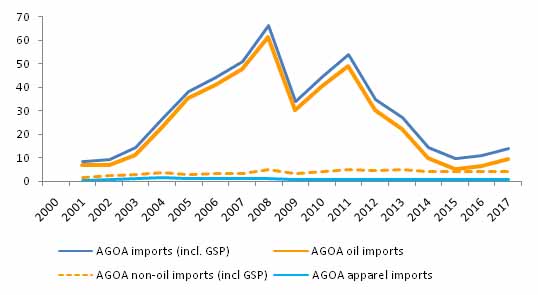

AGOA (including GSP) imports into the US totaled $13.8 billion in 2017, up from $26.75 billion in 2014, 26.8 billion in 2013, and 21.3 billion in 2001. In contrast, the US exported $25.38 billion worth of goods to sub-Saharan African countries in 2014 and 14.1 billion worth of goods in 2017. The deficit was more pronounced in 2008 ($67.5 billion) and 2013 prior to the dip in the commodities market, with $39.29 billion in imports and $23.94 billion in exports. With such trade deficit that Trump has criticised repeatedly, AGOA is a potential subject to particular scrutiny under Trump. Trump has yet to single out AGOA, but his consistent dissatisfaction with previous trade agreements, including the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) signed by Clinton and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, introduced by Barack Obama has created anxiety among African states involved in AGOA about the future of AGOA. Goods Trade between the United States and Sub-Saharan Africa(billions of dollars)

In 2017, leading AGOA import categories were crude oil ($9.5 billion), transportation equipment ($1.3 billion), textiles and apparel ($1.0 billion), minerals and metals ($826.6 million), agricultural products ($552 million), and chemicals and related products ($320 million).AGOA non-oil imports were $4.3 billion in 2017, more than triple the amount in 2001. Several non-oil sectors experienced sizable increases in 2017, including vehicles and parts, apparel, jewelry and parts, cocoa paste, cocoa powder, fruits, nuts, and footwear. South Africa was the largest non-oil AGOA beneficiary in 2017.

In addition to AGOA, the United States also works to promote and enhance the U.S—sub-Saharan Africa trade and investment relationship.This has led to the creation of the African Trade Hubs (rebranded as Trade and Investment Hubs under Obama) to help African companies access AGOA. The U.S. Government provides assistance to African governments and businesses that are seeking to make the most of AGOA and to diversify their exports to the United States—mostly through four regional trade hubs: East Africa Trade and Investment Hub (EATIH), based in Nairobi, Kenya;the West Africa Trade and Investment Hub (WATIH), based in Accra, Ghana;the Southern Africa Trade andInvestment Hub (SATIH), based in Pretoria, South Africa with a satellite office in Gaborone, Botswana.

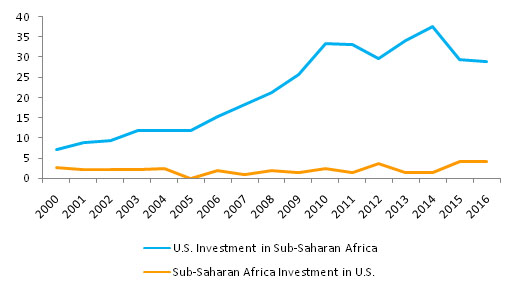

In 2016, Sub-Saharan (SSA) foreign direct investment (FDI) stock in the United States stood at $4.2 billion, up from $1.6 billion in 2014 (164 percent increase) (Bureau of Economic Analysis).U.S. investment stock in sub-Saharan Africa stood at $29 billion in 2016 (Figure 3), down from $37.5 billion in 2014. The three largest destinations for U.S. investment in SSA countries were Mauritius ($6.7 billion in 2016), South Africa ($5.1 billion), and Nigeria ($3.8 billion).

Figure 3. Investment between the United States and Sub-Saharan Africa(billions of dollars)

Since its enactment in 2000, AGOA has been at the core of U.S. economic policy and commercial engagement with Africa. The U.S. Congress requires the President to determine annually, whether sub-Saharan African countries are eligible for AGOA benefits based on progress toward the establishment of a market-based economy, rule of law, economic policies to reduce poverty, protection of internationally recognized worker rights, and efforts to combat corruption.

President Obama pushed a strong democratic agenda and launched half a dozen new development programmes including Power Africa, Feed the Future and the Global Health Initiative. Before him, Bush’s “compassionate” approach led to the establishment of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), two of America’s most widely-praised programmes on the continent.The US relationship with Africa had strengthened significantly under the presidency of Barack Obama, as evidenced by initiatives such as the first US-African Leaders Summit and the US-Africa Business Summit in August 2014, with over 1,000 participants in attendance. One of Obama’s most successful programmes was the Young African Leaders Initiative (YALI),which brings several hundred young African professionals and entrepreneurs to the US for six weeks each summer.Barack Obama signed off on a 10 year extension to the AGOA aimed at creating 350,000 African jobs.

With the attention and congressional interest in promoting U.S. – Africa trade, there appears to be an understanding across the U.S. government that sub-Saharan Africa remains an important market for U.S. businesses and the global economy.

The Obama administration had been working to develop a new trade architecture based on reciprocity that would ultimately replace AGOA’s unilateral preference regime, a point that the U.S.Congress reinforced during the reauthorization of AGOA in 2015 when it expressly instructed the United States Trade Representative (USTR) to pursue free trade agreement negotiations with AGOA eligible countries.This position has taken a centre stage in the discussion since 2016. AGOA establishes the annual U.S.-sub-Saharan Africa Economic Cooperation Forum (known as the AGOA Forum) to promote a high-level dialogue on trade and investment-related issues. Since 2016 the U.S. administrations has engaged Africa through an array of meetings, all of which seem to point to indications that the Trump administration want to transition to a more reciprocal trade agreement to support U.S. exports and investments in the face of the growing dominance throughout Africa of European and Chinese companies.

For example, on September 20, 2017, President Trump hosted a working lunch in New York withHeads of State from Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Namibia, Nigeria, Senegal,South Africa, and Uganda. At the lunch, the President stated his desire to promote prosperity and peace in the region through a range of economic, humanitarian, and security activities, and affirmed the United States would seek to foster opportunities for job creation in both Africa and the United States, as well as to extendeconomic partnerships to countries that are committed to self-reliance.

The theme for the 2018 AGOA Forum 07/11/2018 was “Forging New Strategies for U.S. – Africa Trade and Investment”, and Ambassador Lighthizer in his introductory speech brings out to light anew strategy—the Trump Administration’s desire to negotiate a model free trade agreement with a sub-Saharan African country. The purpose of the forum was to declare the time was now right to pursue a comprehensive and more permanent trade and investment framework to govern trade between the United States and Africa. Ambassador Lighthizer reminded African leaders that AGOA was a precursor for US-Africa trade relation to pave the way for a free trade agreement between the United States and sub-Saharan African countries.

Establishing a more stable, permanent, and mutually-beneficial trade and investment framework with the United States could be transformative for Africa since it has the potential to lock in the benefits of AGOA, bringing the certainty businesses need for long-term business decisions. The U.S. Congress, specifically the House Foreign Affairs Committee has been considering ways to improve and strengthen AGOA. Recently, Chairman Ed Royce and a group of bipartisan committee leaders introduced the AGOA and MCA Modernization Act (H.R. 3445), a piece of legislation, which encourages policies that promote trade and cooperation, while providing much-needed technical assistance to help eligible partners fully utilize AGOA. Given the recent economic trends of embracing regional trade, this legislation also importantly grants the Millennium Challenge Corporation increased flexibility to support regional integration by allowing up to two simultaneous compacts with an eligible country.However, the overwhelming focus of most sub-Saharan African countries with respect to their trade relationship with the United States has been on securing renewal of AGOA rather than seeking other, more far-reaching trade arrangements.Despite bipartisan support, the best hope for AGOA is that it will be allowed to remain in place with declining support until it expires. If there is an effort to reframe it, the US will probably demand African nations open their markets to American goods on a reciprocal basis (Witney Schneidman and Jon Temin).

Currently, Morocco is the only country on the African continent withwhich the United States has an FTA. This focus on potential FTA partners in sub-Saharan Africa is consistent with Congress’s instructions in AGOA’s 2015 reauthorization to seek to negotiate FTAs with sub-Saharan African countries. Africans are rightly concerned about the future of AGOA and its associated benefits. Some expect it will be difficult to continue justifying the one-way trade preference when AGOA expires in eight years.

nnnnn